Dependent yet abusive, enchanted yet careless, man’s relationship with the sentient and non-sentient beings and phenomena of his environment has had a long history of both beauty and violence. Exploring the peninsula of O Morrazo, a verdant corner of Galicia carved out by the mouths of the three river inlets, Lives and Times discovered one particularly bloody chapter in this history of man and the sea, that of whaling: its origins, its industrialisation, and its death.

The whale has long been an object of both fear and fascination in human cultures. Its gigantic proportions inspired the imaginations of generations across the seven seas, with legends and literature born telling tales of sailor-eating, ship-sinking sea monsters. This fear and fascination long gave whaling – a dangerous trade it is true – a feel of romance, adventure, and heroism across the centuries, an aura whose glow faded with the rising realisation of reality in the twentieth century a reality of endangerment and extinction.

When this folkloric fascination for the whale met with modernity – when it found new tools for the hunt, new sails for navigation, new uses for its products, new markets for its consumption – then the catastrophe begun. The first victim of extinction was the Basque or French Whale, long a low fruit to pick for its tendency to come close to shore, close to man, whose hand-held harpoons put it to a species-wide death by the nineteenth century.

With no other predator minus homo sapiens, the cetaceous genus is a particularly vulnerable one for human-induced endangerment and extinction. Its females can give birth to calves only once every three years or so, and its blubber, meat, bones, feeding filters, its oils and intestines, were all highly prized merchandise for consumer markets, being put to use in cuisine, lighting, pharmaceuticals, perfumeries, cosmetics, corsets, umbrellas, soaps, lubricants, candles… Even its bodily fluids were applied in cosmetics, and something known as ‘grey amber’ – a substance which gathered in its stomach from indigestion of krill – was worth, quite literally, its weight in gold for its ability to make perfume aromas last longer. As an old miniature-boat builder told me, “the Massó Brothers took every inch of gold from the whales – nothing was wasted!”

Who were the Massó Brothers? The Massó Brothers were Galicia’s own fishing and whaling family, a bourgeois set from Catalonia responsible for an ever increasing harvest, an ever growing death toll. By their own calculations, the Massó Brothers culled some 5,965 common whales, 6,505 Cachalots (a whale with teeth), and several hundred specimens of the Bowhead Whale and the near extinct Basque Whale.

… Perhaps the human species can redeem itself in returning to a respect for this distant cousin of ours. For the whale, we now know, is much more similar to ourselves than we might have imagined: it sings songs, it has language, it loves and educates its young, shows curiosity and care, and has social norms and culture …

But just as the harvest grew, so too did our collective consciousness of the dimensions and impact of the hunt. By the 1970s environmental groups had pushed the issue onto the front pages, causing widespread public discussion with such bold acts as ship sabotage, sinking, in 1980, one of the Massó Brothers whalers by dynamiting a gaping hole into its hull.

Five years after this act of ship sabotage, the International Whaling Commission prohibited whaling across the globe, leading to the immediate cessation of whaling in Galicia and the eventual bankruptcy of the Massó Brothers empire in 1994. The damage done, however, was enormous, and only now, some thirty two years after the ban, have whales dared return to the sparkling waters of Galcia’s Rías Baixas, with an enormous twenty-four metre Blue Whale recently being spotted passing by Pontevedra.

Elsewhere, though, the slaughter continues in flagrant defiance of the letter and spirit of the moratorium. In 2015 the whaling nations of Japan, Norway, and Iceland captured some 1,600 whales, which in relative terms is a reduction on the 25,000 whales hunted globally in 1980 – revealing the efficacy and success of the ban – but which in absolute terms is 1,600 too many, placing at risk the recovery of these gentle giants.

Whales have long been a mystery to humankind – their sheer size a cause for both awe and fear – but the line which divides an object of fascination and an object of desire is thin, and with the arrival of the market and technology to whaling this lust for lubber took the world’s whales to the precipice. But with the hunt all but over all over the world, perhaps the human species can redeem itself in returning to a respect for this distant cousin of ours.

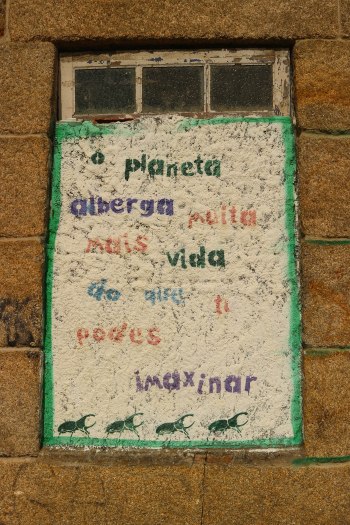

For the whale, we now know, is much more similar to ourselves than we might have imagined: it sings songs, it has language, it loves and educates its young, shows curiosity and care, and has social norms and culture. It should not be hard for us to break down our speciesism at least in regards to the whale with its enormous brain and lifespan – both far larger than our own – and perhaps it is not too much to hope that what begins with the whale can expand to all mammals and beyond into all the kingdom of Animalia.

Lives and Times thanks the Massó Museum for the information in this article and for the two archival photographs displayed. It also thanks the museum for a stimulating visit to the temporary exhibition “The Modern Whale Hunt in Galicia”, which can be visited at the Museo Massó of Bueu, Pontevedra.

Lives and Times recommends…

- The Mysteries of the Humpback Whale – The Ocean’s Gentle Giant – Radio National Australia Broadcast – Conversations with Richard Fidler: Wally Franklin

- Recordings of Whale Songs from The Oceania Project – iWhale

Reblogged this on Cleaning Service in the Stockholm.

LikeLike